Author: Josip Osrecki

I often find that managers associate the word “leadership” with sharing a vision and giving direction – which is true. But they often fail to understand what their domain of control is – what do they manage and how does their leadership really manifest itself?

The main question I like to ask is: What should they not try to control but rather support?

If control is applied to something that should be supported, it can greatly undermine any agile transformation initiative.

And when I say “support” – it includes all the usual suspects:

- Empowering teams to decide how the product will be built

- Building your leadership backlog that contains initiatives for improvement for the underlaying (often technical) infrastructure that supports the long-term strategy of the organization

- Being aware of the capacity (people and resources), potential bottlenecks and which initiative will bring the most value

- Implementing bottom-up feedback loops so that everybody can easily raise potential concerns and get support in solving them

- Encouraging knowledge sharing between teams

- Giving time for creativity and experimentation – the most probable way towards technological or business breakthroughs

I believe that not knowing how to support your employees causes damage on two levels. Firstly, when employees do not have the tools or skills to do the job. And secondly, when the manager acts in a way that is not in line with agile values. They do not do it because of spite – it is a simple regression to doing something they already know and are good at – even if that is micromanagement or asking for the latest status report.

Let me share several examples where I found poor leadership skills had a serious negative impact on business.

Not noticing one of the backbones of infrastructure has grown from shadow IT

To perform security testing there was a need for dozens of different token types. One small development team initially created a token generator tool that enabled token generation with a few simple clicks. And it worked only for their test environment. The word spread and testers from other teams asked to add support for their environment as well. Since this was not an “official” tool, it was deployed on some rouge machine nobody but devs knew anything about. And nobody really cared until one day that machine was accidentally shut down, causing a complete halt of testing and development for several hundred people for that and part of the next day. This is a great example of how a good initiative can work against the business rather than for it because it’s not understood, cultivated, and lead properly.

Choosing quick fixes over investment in automation

In most cases, motivated knowledge workers want to work smart, not hard. Naturally, they try to automate tasks that are boring and repetitive so they can focus on more complex tasks at hand. Simple as it sounds, in project-oriented organizations, there is usually little understanding for automation if ROI does not justify it within the project’s scope. Although there are times when common sense prevails, often the person trying to improve and automate the process is held in contempt by managers who can’t see beyond “their” project.

Bank’s ATM running on rouge VM

Yes, it is as scary as it sounds. An extreme example of being blocked by a corporate “budgeting” rule where not spending a 100$ could easily result in millions $ damages (not mentioning the reputation). Management simply did not allow buying a few extra licenses because the budget for that year was already spent. That combined with some production issues resulted in the developer deploying and maintaining a crucial part of banks software on an unlicensed Windows server. Although resolving this should be easy and common sense, “leadership” did not do anything about it for months.

Failing to notice blocked communication channels

Years ago, I ran into an extreme example of lack of communication within the team. Testers who came from different external vendors were not allowed to share test scenarios and, in some cases, even talk to one another although they were working towards the same goal. Some people within the team did warn about this, but no actions were taken until some serious bugs went to production. The point here is that a good leader should notice these kinds of problems, act as an information flow catalyst and encourage cooperation both within and between teams.

Leaders build a great long-term vision and let others help them achieve it

These opportunities and problems have the same thing in common – they came from people building the solution and not from the business side. Somebody failed to listen to the people that have experience building the thing (whatever it may be) and advocate their ideas to help both the team and the organization.

The argument many managers have is that they do not understand the technical side of things and therefore cannot advocate ideas that come bottom-up. My answer is always the same – you do not need to know how to code, but you do need to know the implications and try to understand the complexity of the “technical side” so that you can prioritize team backlog (or company portfolio) considering current (and future!) technical capabilities.

If Daniel Pink’s book Drive is to be believed, simply providing vision and purpose is not enough. You also need to help people take ownership of their ideas and give them autonomy. Instead of imposing technical standards and ways people communicate, let those grow organically. The role of a leader is to support people and ideas and, metaphorically speaking, to kill the weeds that are slowing down their growth.

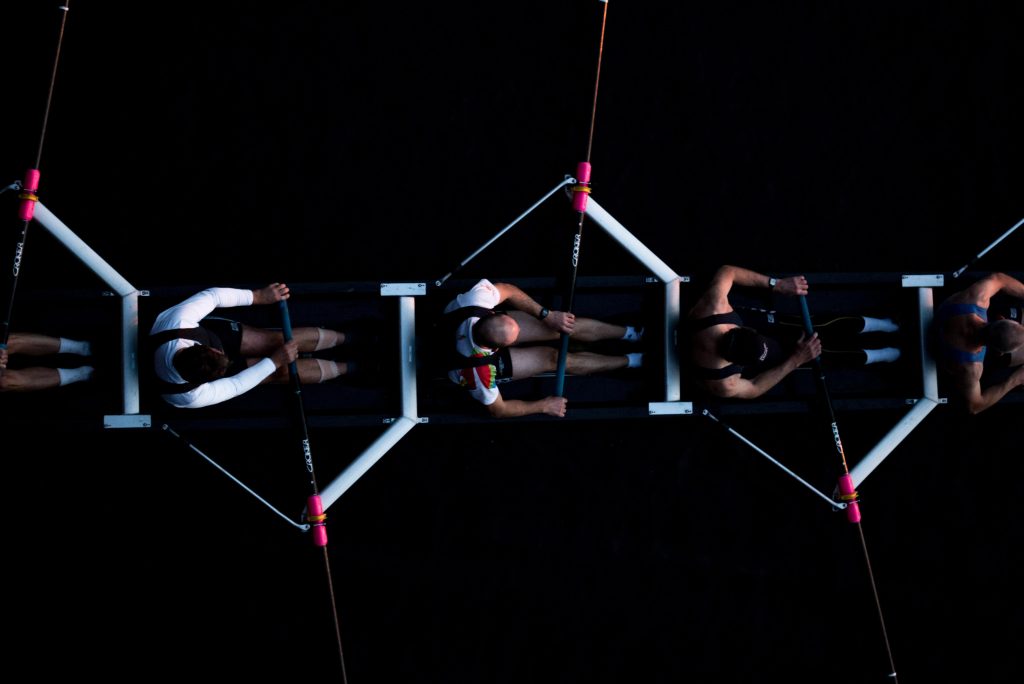

Structure and standards are not a bad thing – you need to plan how you want the organization and people to grow. But at the same time, watch out not to overdo it. If you know anything about gardens, you could compare it to planning a French vs. English style garden. The former is trying to control nature to fit a particular shape, while the latter tries to work with the landscape allowing more creativity and wilder foliage.

For years organizations tried to mimic the French gardens. Unfortunately for them, people turned out to be even more complex than plants. Let us admit, scary as it may be, that controlling every aspect of an organization is impossible. Instead, build a great long-term vision and, while ensuring some enabling constraints are in place, allow others to help you cultivate it.

Photo by Phillip Glickman on Unsplash.

Falls Sie Fragen haben, sind wir nur einen Klick entfernt.