We all know the learning methods we adopted when we were in school – cramming, rereading the text, underlining, and overcoming new material in chunks. Recent research shows that most of these do not work. Read why and discover some evidence-based strategies for effective learning.

Myth #1 – Cramming

We’ve all done it. We needed to learn something before a big test, or a meeting, or a project kickoff — so what do we do? We wait until the last week, day, or even the last hour, to get started. After all, if we memorize information too early, we might forget it till we need it. It’s best to have it fresh in our minds. Right?

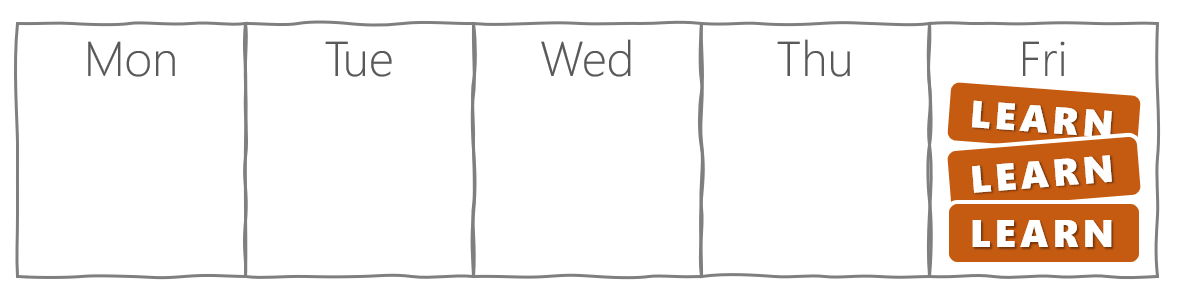

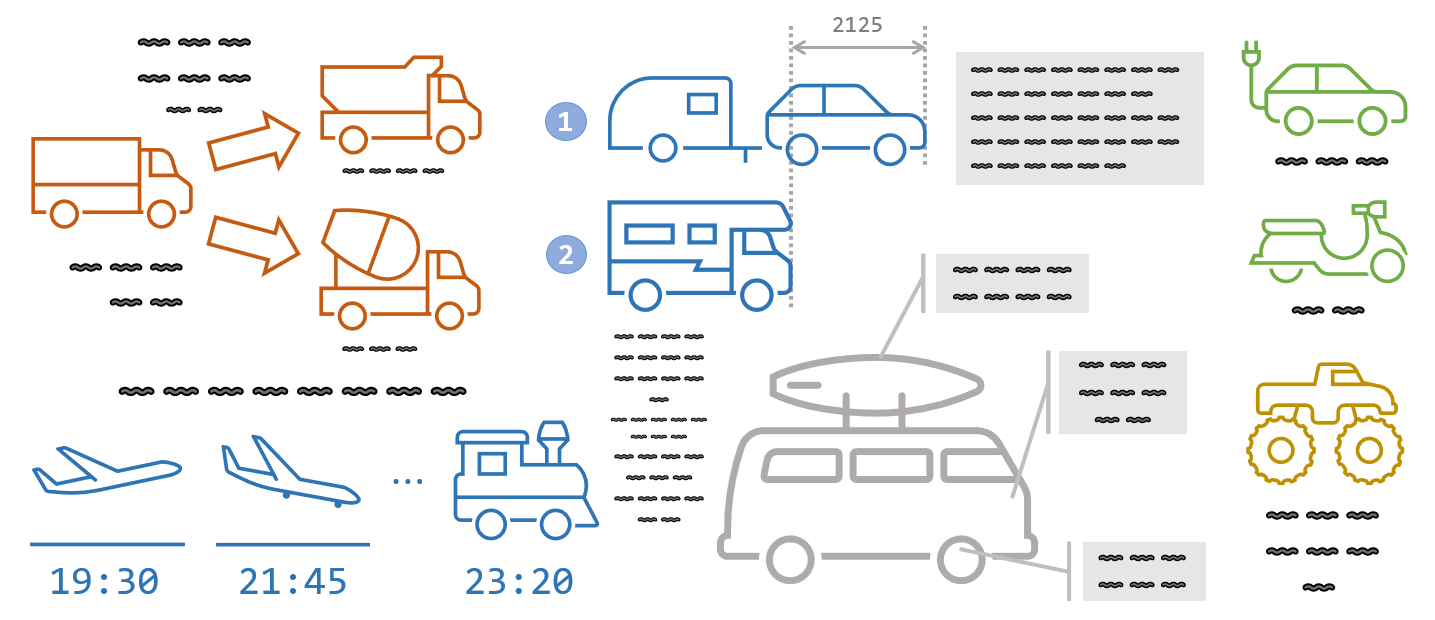

On Monday you find out you need to learn something by Saturday morning. You wait till Friday evening, then spend three hours cramming.

Wrong. Cramming works in the short term, but the memory of what you learned will not be durable. The speed of forgetting will be proportional to the speed of acquiring knowledge. If you want the information to stick — don’t cram.

Instead – Try Spacing

Spread out the learning process through your available time – a technique known as spacing in the scientific literature. You will remember the things you have learned longer. Brain imaging shows that spacing out learning increases brain activity which helps us to incorporate new knowledge.

It’s better to start learning at once, and to spread out the three hours you have assigned for learning throughout the week.

Furthermore, our brain is working on incorporating new information even when we are not actively learning. It is processing the information subconsciously, consolidating and reorganizing internal storage for easier retrieval later. The brain does this even when we sleep — it appears to be the primary function while sleeping. It takes time to do its magic, and during that time, we also need to keep refreshing and adding new information in regular intervals.

Myth #2 – Rereading

If we want to remember the information we just read better, what do we do? We read it again. And maybe again, or as many times as necessary. However, research shows that reading the text twice does not improve the long-term retention of its content.

This runs counter to our intuition. As we repeatedly read a single passage of text, we become more fluent in this activity. But short-term fluency is not long-term retention. When our brain encounters familiar information, it reduces attention. We become overconfident in our knowledge because we confuse this familiarity in the working memory with the true knowledge from the long-term memory.

In one study, students were divided into two groups and given different assignments:

- Read the assigned text four times.

- Read the text only once, and then try to write down everything you remember three times.

Students who read the text four times were more confident in how much they remember. However, when tested one week later, the students who spent their time remembering instead of rereading did better on the test.

Instead – Try Retrieval Practice

If you want to be able to recall important information better, practice recalling that information. Sounds logical, right? Also, when we try to recall information from memory, we make that memory stronger.

To practice retrieval, you can list things you remembered from the educational material, draw diagrams, or test yourself by answering questions.

There are many ways to practice retrieval from memory. Take quizzes on the topic, draw diagrams and mind maps, write out as many sentences with everything you can remember, build a deck of flashcards, record a video tutorial, or give your mother a call — she might be interested in listening to what you have learned

Myth #3 – Learning styles

Here’s one myth that seems to be very popular – learning styles. This idea implies everyone has a different way of absorbing knowledge. Maybe you are a visual learner, and you can understand new information the best when presented in diagrams, schematics, and mind maps. Or perhaps you learn better by listening to the spoken word, so you use auditory material, like recorded lectures or YouTube tutorials. Some people acquire knowledge by experimenting on their own, while others thrive in a social context and learn best in groups. Choose an appropriate style for every individual, and you will improve their performance.

While it is true that some people might at times prefer one learning modality over another, literature reviews and meta-analyses showed no improvement when matching educational materials to the learning styles of students. Therefore, modern cognitive science has moved away from the concept of learning styles.

Instead – Try Dual Coding

Take advantage of dual coding – a practice of using both verbal and visual channels when learning new material.

It turns out we generally remember pictures better than words. Research suggests that two formats – text and graphics together, allow us to remember the information easier. While presenting, it’s best to include many visual representations that communicate the same ideas as your narration. Just be careful not to distract the public with irrelevant or obtrusive details.

Combining graphics with textual information is best for learning.

Myth #4 – Chunking

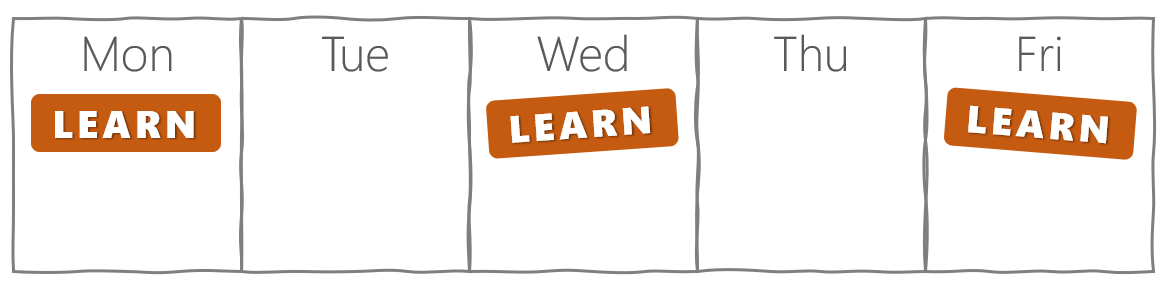

We tend to group similar material into sets or segments. We start with the first segment and work on it exclusively. After we are satisfied with our proficiency in the first segment, we set it aside and concentrate on the next problem or topic. We conquer one segment at a time. Well, it turns out that may not be the best use of your time.

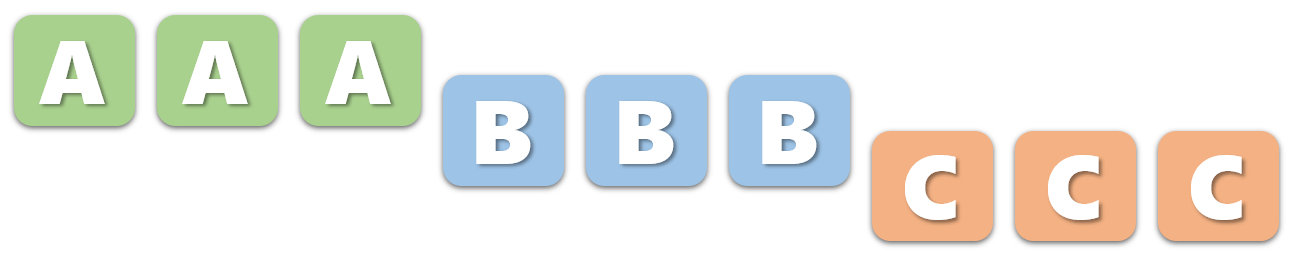

Chunking material will group all activities for topic A first, then follow with all of B, and finally all for C.

Instead – Try Interleaving

Instead of processing materials by subject or type sequentially, mix them up like shown in pictures. This type of learning is called interleaving, and it produces better results.

It’s more challenging to switch context in such a way, but that’s the point. We don’t want our brains to lay away, push aside, or even dismantle newly constructed cognitive facilities. To keep these facilities active, we return to them and put them to work again, and again.

Interleaving also incorporates spacing, since learning of connected concepts is spread out in time. In the moment of learning, it might not feel like an improvement, it might slow you down or you might be less productive. However, in the long run, better results are guaranteed.

Overarching Principle – Desirable Difficulty

Many of the approaches described here are heavily influenced by the effect called “desirable difficulty”. We don’t want learning to become too easy because what comes easily, goes easily. The truth is, we are typically quite lazy when it comes to any mental activity, especially while learning new things. Rather than exerting itself, our brain looks for shortcuts and temporary solutions whenever it can. Therefore, we need to put in some effort to reach optimum working temperature.

Our brains need to be challenged, but also relatively successful in all their tasks in order to be the most efficient. We should find the balance, so we don’t frustrate nor relax our brains and brains of our students. This is an active process of learning optimization and adaptation of challenges to our level of proficiency.

Read more

If you want to dig deeper into modern research on learning, we recommend the following books:

- “Understanding How We Learn: A Visual Guide” by Yana Weinstein and Megan Sumeracki, with illustrations by Oliver Caviglioli

- “How We Learn: The New Science of Education and the Brain” by Stanislas Dehaene

- “Powerful Teaching: Unleash the Science of Learning” by Pooja K. Agarwal and Patrice M. Bain

Check out the CROZ learning courses we organize to help you keep up with the technological changes.

Photo by Firmbee.com on Unsplash.