A Deep Technical Guide to KubeVirt, Architecture, and Automation

In the first part of this series, Mate explored the business perspective of moving from VMware to OpenShift Virtualization and why organizations are increasingly considering a shift toward platforms built on open-source principles.

This second article turns to the technical side. If you’ve heard terms like KubeVirt, CRDs, GitOps, or MTV and wondered how they fit into the bigger picture, this blog is for you.

We’ll break down how OpenShift Virtualization works, what it’s built on, how it compares with VMware concepts you already know, and why the biggest challenges aren’t purely technical, but organizational.

Open Source as a Foundation

Red Hat’s Commitment to Open-Source

Red Hat’s upstream-first philosophy is one of the most important aspects of its product strategy. Every Red Hat product has a fully open-source upstream community project where innovation happens in the open before being hardened for enterprise use.

- Red Hat Enterprise Linux is built from Fedora

- OpenShift comes from OKD

- OpenShift Virtualization originates from KubeVirt

This model ensures transparency, avoids vendor lock-in, and allows enterprises to consume innovation at a predictable pace. Also, having access to source code can sometimes help with debugging strange behaviors that you might experience while using products (trust me, I’ve done this multiple times, and it’s very helpful.)

KubeVirt: The Foundation of OpenShift Virtualization

KubeVirt is the open-source project that enables OpenShift to run virtual machines natively alongside containers. Rather than being a separate hypervisor platform, KubeVirt is delivered as an operator that can be installed on an existing OpenShift cluster.

From a deployment perspective, this is an important distinction. OpenShift Virtualization does not require a separate infrastructure stack. Instead, it extends the capabilities of a standard OpenShift installation. The primary prerequisite is that the cluster includes bare-metal worker nodes in the node pool. These nodes provide access to KVM, which is required to run virtual machines efficiently.

At its core, KubeVirt uses QEMU/KVM as the underlying virtualization runtime. QEMU is responsible for emulating hardware devices, while KVM provides near-native performance by leveraging CPU virtualization extensions. This combination is well-known and widely adopted across the Linux ecosystem. Red Hat brings extensive, long-term experience with KVM, having previously built and supported enterprise virtualization platforms based on Red Hat Virtualization (RHV), a now-discontinued product whose technology and operational knowledge strongly influenced the evolution of OpenShift Virtualization.

What makes KubeVirt unique is how this virtualization layer is composed into Kubernetes. Each virtual machine runs inside a pod, often referred to as a virt-launcher pod. Inside that pod, QEMU runs the virtual machine process, while Kubernetes remains responsible for scheduling, lifecycle management, health checks, and resource allocation.

OpenShift Virtualization Architecture Overview

With KubeVirt deployed as an operator and QEMU/KVM integrated into the cluster, OpenShift Virtualization becomes a natural extension of the OpenShift control plane. Virtual machines are no longer managed by a standalone hypervisor stack but are instead scheduled, operated, and observed through Kubernetes and OpenShift primitives.

This architectural approach is the key difference compared to traditional virtualization platforms and the source of both its power and its learning curve.

How OpenShift Virtualization Runs Virtual Machines

From an architectural perspective, OpenShift Virtualization does not replace Kubernetes, it builds on it.

OpenShift Virtualization introduces the ability to run virtual machines by layering virtualization capabilities on top of Kubernetes primitives. Key components include:

- HyperConverged (HC) CRD:

The main resource that enables virtualization capabilities inside of OpenShift. All global configuration of cluster is defined on HyperConverged resource (e.g. CPU overcommitment, live migration configuration, default storage classes for transient states (vTPM, …). - VirtualMachine (VM) CRD:

Declarative definitions of VM configuration - VirtualMachineInstance (VMI) CRD:

Running definition of VM instance. - virt-handler:

A daemon on each node responsible for handling VM lifecycle operations like start, stop, health checks. - CDI (Containerized Data Importer):

Handles importing, uploading, and cloning VM images. - AAQ (Application Aware Quota):

Specialized quota validator for VM specific workload (more on this later) - virt-launcher:

A pod that runs a QEMU/KVM instance. Each VM gets its own pod.

A VM in OpenShift is a pod with a virtualization layer, not a separate construct. This allows for unified scheduling, monitoring, and automation.

Mapping OpenShift Virtualization to VMware Concepts

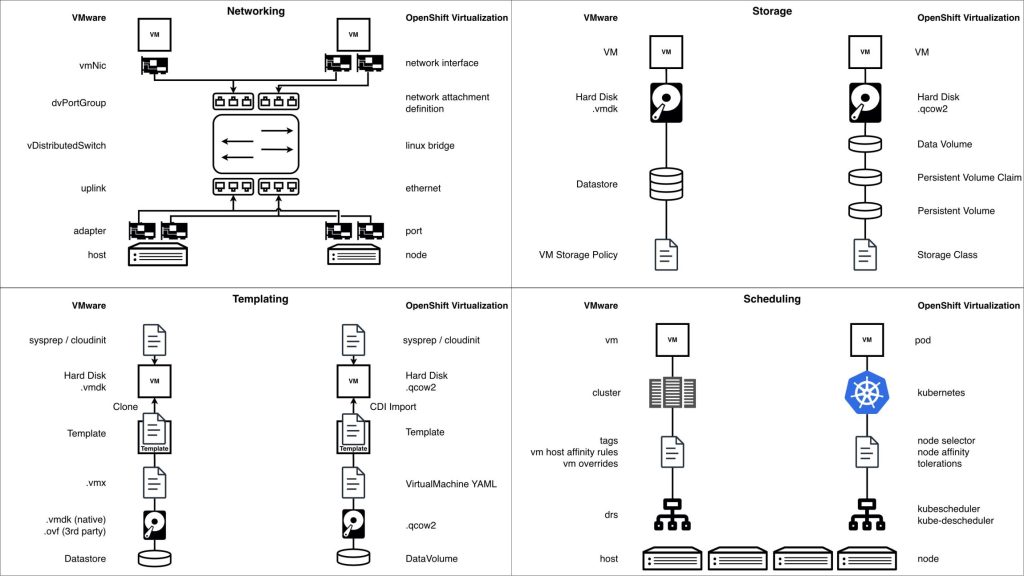

While a one-to-one comparison isn’t fully accurate (we’ll return to this in Section 5), it helps to connect OpenShift concepts to terms VMware admins already recognize:

Networking in OpenShift Virtualization

Networking in OpenShift Virtualization follows Kubernetes-native principles while still supporting traditional virtual machine requirements. This hybrid model is powerful, but it also introduces important differences compared to classic hypervisor-based networking that infrastructure teams must understand early.

Every virtual machine in OpenShift Virtualization is connected to the Pod Network by default. The Pod Network is provided by the cluster’s primary CNI plugin, most commonly OVNKubernetes, and plays a foundational role in VM connectivity. It enables native communication between virtual machines and container workloads, integrates VMs into Kubernetes services such as DNS and routing, and allows platform features like load balancing and service exposure to work consistently across workload types. From inside of VMs guest operating system, the Pod Network appears as a standard network interface, but from the platform perspective it ensures that virtual machines participate fully in the Kubernetes networking model.

In addition to the Pod Network, OpenShift Virtualization supports secondary networks through Multus, allowing virtual machines to attach to multiple network interfaces. These additional interfaces are defined using NetworkAttachmentDefinitions (NADs) and are commonly used for VLAN-backed networks, traffic separation or integration with external systems. Each secondary network is exposed to the virtual machine as a standard NIC, preserving compatibility with traditional VM networking expectations while remaining declaratively managed.

For advanced networking scenarios, there is the NMState Operator, which is frequently used in OpenShift Virtualization deployments. NMState enables declarative, node-level network configuration, including interface bonding, VLAN creation, and consistent interface mapping across worker nodes. This is particularly important when preparing nodes for Multus-based networking, as it ensures predictable and uniform network behavior across all nodes capable of running virtual machines.

Network security follows Kubernetes enforcement models. Kubernetes NetworkPolicies currently apply only to the Pod Network interface of a virtual machine, as policy enforcement is provided by OVNKubernetes. Secondary network interfaces attached via Multus are not subject to NetworkPolicy enforcement today, meaning segmentation for those interfaces must rely on VLAN isolation, external firewalls, or network design controls. This limitation is well understood and is an active area of development, with future enhancements expected to extend policy enforcement capabilities to additional VM network interfaces.

Storage in OpenShift Virtualization

Storage is often the biggest unknown factor when organizations assess OpenShift Virtualization for the first time. While compute and networking concepts map relatively cleanly from traditional hypervisors, storage introduces a different operational model that requires careful evaluation, especially in existing enterprise environments.

In OpenShift Virtualization, virtual machine disks are backed by Kubernetes Persistent Volumes (PVs), which are dynamically provisioned through StorageClasses and implemented by a Container Storage Interface (CSI) driver. This abstraction allows OpenShift to integrate with a wide range of storage backends, but it also introduces an important prerequisite: the storage platform must have a fully compatible and well-tested CSI driver.

Not all CSI drivers provide the same level of functionality. When assessing storage for OpenShift Virtualization, it is critical to validate support for features such as:

- Block and filesystem volume modes

- Volume expansion

- Snapshot and clone operations

- Performance and latency characteristics

- Live migration compatibility

- Disk encryption

- DR replication capabilities

- Backup

One of the most significant conceptual differences compared to VMware is how storage is mapped at the backend level. In VMware, a datastore typically corresponds to a single LUN, and multiple virtual machines, and their disks, are carved out inside that shared construct. In OpenShift, each Persistent Volume usually maps to a separate LUN on the backend storage system.

This has important implications:

- A virtual machine with two disks will typically consume two separate LUNs

- Large VM estates can result in a high number of backend LUNs

- Storage teams must account for LUN limits, provisioning models, and operational practices

This shift does not represent a limitation, but it does require storage architecture awareness and planning. Some storage platforms handle large numbers of LUNs efficiently, while others require tuning or architectural adjustments.

Tooling, Automation, and the Ecosystem

OpenShift Virtualization does not exist in isolation. One of its strongest advantages is that virtual machines immediately benefit from the broader OpenShift ecosystem, which is built around automation, declarative configuration, and API-driven operations. OpenShift itself is designed as an operator-driven platform, where new capabilities are added by deploying operators that encapsulate application logic, lifecycle management, and upgrades. OpenShift Virtualization follows this same model and integrates seamlessly with other operators for storage, networking, security, observability, and automation. This makes it possible to expand a cluster incrementally, enabling only the functionality that is required.

At the same time, this flexibility introduces an important operational consideration. Every additional operator is another component to manage, with its own lifecycle, resource consumption, upgrade path, and failure modes. While operators significantly simplify installation and maintenance compared to traditional manual approaches, they still require understanding and ownership.

Migration Toolkit for Virtualization (MTV) and Containers (MTC)

The Migration Toolkit for Virtualization (MTV) is the primary and recommended mechanism for migrating virtual machines into OpenShift Virtualization. It is designed specifically to move VMs from VMware and other supported virtualization platforms in a controlled, repeatable, and scalable way, minimizing manual effort and reducing risk during migration.

MTV handles the full migration lifecycle, including source environment discovery, VM inventory, network and storage mapping, disk conversion, removal of VMware guest tools, installation of KVM guest tools, and VM creation on the OpenShift side. Because it integrates directly with OpenShift APIs, it fits naturally into automated and declarative workflows rather than relying on one-off, manual operations.

Depending on the number of virtual machines being migrated and the performance characteristics of the environment, MTV can be configured to use a dedicated network for migration traffic. This approach helps isolate migration workloads from production traffic and provides more predictable performance during large-scale migrations. Importantly, this dedicated migration network is advisable to be planned and configured during cluster creation, as it relies on underlying network design decisions.

MTV supports the concept of migration waves, which represent iterative bulk migrations of multiple virtual machines grouped together based on business, application, or technical criteria.

Waves allow organizations to:

- Validate migration processes incrementally

- Prepare internal scripts/processes to support new target environment

- Reduce risk by migrating what workload is migrated when

- Coordinate cutovers in a structured manner

- Roll back or adjust strategy between iterations

In large enterprise environments, these migration waves are typically easier to coordinate when integrated with the Ansible Automation Platform. Ansible can orchestrate pre-migration checks, inventory preparement, post-migration validation, and application-level configuration across hundreds or thousands of virtual machines.

For smaller environments or limited numbers of virtual machines, MTV can also be used manually through the OpenShift console without additional automation tooling.

The Migration Toolkit for Containers (MTC) currently plays a role in storage migration scenarios, particularly when persistent data must be moved between storage backends as part of the virtualization migration process. While MTC is a required dependency in some workflows today, this dependency is expected to be removed in the future as storage migration capabilities are consolidated into MTV or core OpenShift tooling, further simplifying migration architectures.

The Human Side: Migration Is Not Just a Technical Problem

After reviewing architecture, networking, storage, and tooling, it becomes clear that migrating to OpenShift Virtualization is not only a technology problem. The platform is mature, the tooling is capable, and the architectural patterns are well defined. In practice, the biggest challenges arise from people, processes, and mindset, not from missing features.

Organizations often approach OpenShift Virtualization expecting it to behave like a traditional hypervisor platform. This expectation leads to friction. While many familiar concepts exist (virtual machines, networks, storage, live migration) the underlying operating model is fundamentally different. OpenShift Virtualization is built on OpenShift and Kubernetes, and that foundation brings prerequisites, assumptions, and workflows that do not exist in classic VMware environments.

A common pitfall is attempting a one-to-one comparison between hypervisors. OpenShift Virtualization should not be evaluated as a direct replacement for vSphere feature by feature. VMware is a hypervisor-centric platform designed around imperative operations and centralized management. OpenShift Virtualization, on the other hand, is a Kubernetes-based application platform with virtualization capabilities layered on top. As a result, Kubernetes concepts such as declarative configuration, reconciliation loops, and cluster-level operations are not optional, they are core to how the platform works.

This difference has direct implications for teams and roles. VMware administrators are not becoming obsolete, but their skill sets must evolve. Operating OpenShift Virtualization effectively requires familiarity with Git, YAML configuration and Kubernetes fundamentals. Tasks that were previously performed through graphical interfaces are now expressed as code and managed through pipelines and automation.

Training plays a critical role in making this transition successful. Without structured enablement, teams often struggle to connect existing virtualization expertise with Kubernetes-native operational models. Investing in hands-on education early significantly reduces friction, shortens adoption timelines, and increases confidence across teams.

At CROZ, we have prepared a structured training and enablement program to help organizations build the skills and confidence required for a successful migration from VMware to OpenShift Virtualization:

- Docker & Containerization Course

- Kubernetes Course

- Kubernetes Certification Training: CKA or CKAD Exam Prep

- OpenShift Course

- OpenShift Virtualization Training: Modernizing Workloads

- VMware Workshop: Exit Strategy & Alternative Platforms

- Ansible Fundamentals

Equally important is the organizational aspect. Successful migrations require collaboration between infrastructure, platform, storage, networking, and automation teams. Clear ownership models, shared responsibility for operators and platform components, and investment in training are essential. Teams that treat OpenShift Virtualization as “just another hypervisor” often struggle, while those that embrace it as a platform transition unlock long-term benefits in consistency, scalability, and operational efficiency.

Conclusion

OpenShift Virtualization represents a fundamental evolution in how virtual machines are deployed and operated. Built on open-source foundations, powered by KubeVirt and QEMU/KVM, and deeply integrated into the OpenShift platform, it unifies virtual machines and containers under a single, declarative operational model. The architecture is mature, the tooling ecosystem is robust, and the platform continues to evolve rapidly.

However, as this article has shown, success with OpenShift Virtualization is not defined solely by technology. It requires a clear understanding of Kubernetes-based architecture, careful attention to networking and storage design, disciplined use of automation and operators, and, most importantly, investment in people and skills. Organizations that approach this transition as a platform transformation rather than a hypervisor swap are far better positioned to realize its full value.

This brings us naturally to the next step in the journey.

In the next blog in this series, we will step back from the platform itself and focus on what often determines success or failure long before the first virtual machine is migrated: planning and assessment. We’ll explore why the assessment phase is critical, why it should focus less on OpenShift Virtualization and more on third-party integrations such as storage and backup, and how organizations build a clear, realistic picture of their existing VMware landscape. We’ll also look at how migration roadmaps are typically designed, how tooling like RVTools fits into the process, and why persona mapping and employee training must be treated as first-class inputs, not afterthoughts.

If you’re serious about a successful VMware takeout strategy, that assessment phase is where everything truly begins.

Stay tuned!